The Noblest of Pines

I went up to Pine Mountain the other day. I needed to see some tall trees, to walk among conifers, to smell that pine-forest-in-summer scent. I find that I need to do this from time to time, and Pine Mountain, one of Ventura County’s hidden gems, is easier to get to than the spectacular conifer forests perched above the Los Angeles Basin in the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains; they require fighting through LA traffic. Like those mountains, Pine Mountain is part of the Transverse Ranges, formed when tectonic plates collided, rotated and compressed, resulting in east-west trending ranges rather than the more typical north-south ones. The colder north-facing slopes of these ranges hold conifers, and that’s what draws me.

Pine Mountain itself is still remote enough and far enough to make this a most-of-the-day outing. I drove up Highway 33, the Maricopa Highway, which climbs up out of Ojai, following the Ventura River, its tributary Matillija Creek and finally Sespe Creek until it crests at the turnoff to Pine Mountain. This is steep, rugged country, covered in chaparral, with sycamores and cottonwoods lining the creek sides and river bottoms. Green now, they will turn golden soon, providing a little bit of fall color to these southern California Mountains.

There was little traffic on the 33, on a Wednesday. A few anglers parked by the side of the road, seeking the steelhead trout which inhabit the Ventura River and Sespe Creek. There are a few old ranches up top, perhaps abandoned, as is the summit restaurant and bar. The road to Pine Mountain turns off at the summit and follows a ridgetop, winding in and out of cuts. It is one-way, mostly, so I am careful around the curves, but there is no oncoming traffic on this weekday. The road turns to dirt and rocks at one point. It passes two campgrounds, their campsites nestled among the big rocks; downslope are the massive white rocks of the Piedras Blancas. This is US Forest Service land, part of the massive Los Padres National Forest, and, as usual, they’ve done a great job with the campgrounds. But there was no one at the campsites, and no cars parked at the trailhead. And that was fine by me.

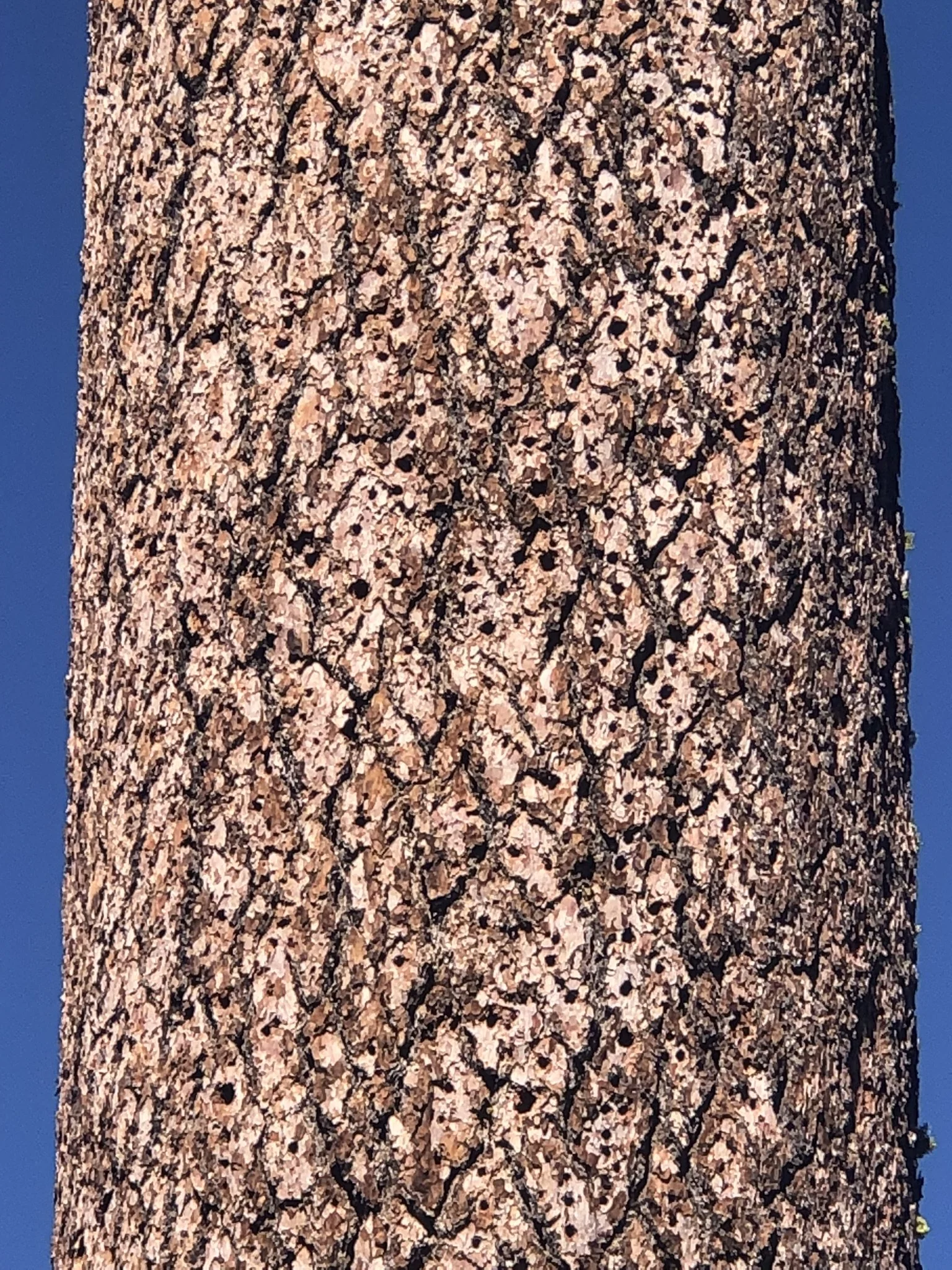

By this point I was at almost 7,000 ft elevation, a rarity in Ventura County, and an elevation I definitely associate with pines. During grad school I lived in Flagstaff, Arizona, which sits at that elevation and is smack dab in one of the largest stands of ponderosa pine forest in the West, in the Coconino National Forest. You’ve seen ponderosa pines. They’re the most ubiquitous of the “yellow pines” in the West, tall and long-needled, with big orange-yellow plates of bark. But they don’t occur here on Pine Mountain, where the rocky conditions favor their cousin, the Jeffrey pine. The two species are very similar, and you can tell them apart by their cones, easily visible in the forest litter under the trees. Ponderosa cones are relatively small and have sharp spurs on the scales (“prickly ponderosa”); Jeffrey cones in contrast, are larger, and lack sharp spurs (“gentle Jeffrey”).

Jeffrey pines line the road to the trailhead and the beginning of the trail. I stop at the first good-sized Jeffrey and stick my nose into one of the deep furrows between the bark plates. I inhale deeply, catching a strong whiff of butterscotch. Chemically, these are esters, and they are volatilized in the warm sunlight of summer, giving a western pine forest its characteristic scent, to which I’m somewhat addicted. This is another way to tell Jeffreys from ponderosas, which smell more like vanilla.

But I’m not here necessarily for the Jeffrey pines, nor am I here to bag Reyes Peak, the trail to which I skirt. I’m after bigger quarry. Literally. I want to see, to walk among, the immense sugar pines. Excluding redwoods and sequoias, sugar pines are the monarchs of the Pacific Coast forests. They are massive, and one fieldbook calls them the most magnificent of the western pines. Can’t argue with that. Sugar pines grow up to 200 ft tall, and can be 6-7 ft in diameter. Said John Muir himself: “This is the noblest pine yet discovered, surpassing all others not merely in size but also in kingly beauty and majesty”.

They are further along the trail, and for me today this is less a trail hike than a stroll. I encounter other trees, such as the white fir, fellow resident of Jeffrey pines in many parts of the Sierra. Past the turnoff to Reyes Peak the trail begins to contour gently along the northern slope of the ridge, and I’m in the sugar pines. They like the colder north-facing slope, where snow lingers longer in winter and spring. All the same, this is somewhat marginal habitat for them, and Pine Mountain is one of a handful of places in the southern California mountains which harbor sugar pines. The bulk of the species’ distribution is in the northern Sierra and the Cascades of southern Oregon; their southernmost occurrence is in the San Pedro de Martir mountains of Baja California. I first encountered them, fell in love with them, in the Lake Almanor area, near Lassen, where my family vacationed when I was young.

Sugar pines are unmistakable, hard to miss, with their large size and long branches sweeping down from their trunks. The upper crown is sometimes truncated; the trees appear tired, maybe, from holding up those branches, and the weight they carry: the most massive cones of any pine. As long as two feet, they dwarf all other cones, hanging pendant-like from the branches, like Christmas ornaments, and piling on the ground under the trees.

I am in the big pines now. It is quiet, cathedral-like, evoking both the respect and hushed quiet you’d expect in one. Sounds are muffled, but the wind, not apparent at ground-level, blows through the treetops. John Muir used to climb tall trees and let the wind carry him back and forth. I will not be doing anything of the sort today. I just bask in the quiet, marveling at the size and number of the giants. Upslope to the south the stand is crowded and trees block out the sky. Downslope to the north, scattered sugar pines frame a view of the lunar landscape of the Cuyama Badlands, pocked with dimples like a golf ball. This is condor country, and the Badlands abut the northern edges of these Santa Ynez Mountains, which hook around and join the southern Sierra to the east. Below me and to the right is the 14,000-acre Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge, established expressly for condors, no visitors allowed there. I visited my daughter Carrie there last spring, when she was working at the refuge for the USFWS condor recovery program, and I saw the giant birds (“can be mistaken for small airplanes”, say the field guides) soaring above, and at the refuge’s condor pen. They are ancient, revered by the local Native Americans. Their numbers have been decimated by habitat destruction and lead bullet poisoning (from the carcasses they feed on), and so condors were one of the first species designated as endangered. They are worth every penny that goes into their recovery.

No condors at Pine Mountain today, though. But other feathered denizens of the pine forest are here, and my friend Merlin helps me detect them. Merlin is a brilliant app which records bird calls and identifies the callers to species. I have been observing birds for over 50 years at this point, ever since grad school and then throughout my career as a wildlife biologist, but my hearing isn’t what it used to be. No problem – Merlin picks up bird call and songs which are too faint for me to hear. Still, my old ears – and eyes – detect typical forest residents: flocks of dark-eyed juncos, with their executioner-style black hoods, mountain chickadees (“chick-a-dee-dee-dee”), and the soft honks of nuthatches. I hear the faint nasal honk of a red-breasted nuthatch; Merlin alerts me to its cousin, the pygmy nuthatch, smallest of the nuthatches, as its name implies. There is a brown creeper on the bole of the tree in front of me. Creepers and nuthatches are gleaners, working the trunks of conifer trees in search of insects in the bark crevices, and efficiently dividing up the work: nuthatches work their way down the trunk, creepers only climb up.

A dead conifer tree (a snag, as the Forest Service calls it) stands upright in a small clearing and is the object of attention for many birds, due to the insects which have taken up residence in it. A gallery of woodpecker holes pocks its lower trunk. All this reminds me that this is a biological community, a part of an ecosystem, with the trees and birds and insects all interacting with each other and with the physical environment, the altitude and soil and slope and weather. Evolution has honed each species’ ability to survive and thrive here. At my feet is a sugar pine cone which a squirrel has stripped of its scales and seeds, providing nourishment to the squirrel and distributing the seeds for the sugar pine, through the squirrel’s scat; its digestive system scarifies the seed, removes its seed cover, prepares it for germination. The ecosystem at work.

Merlin picks up a species that I have little hope of seeing or hearing myself: a northern saw-whet owl, apparently hooting softly somewhere out there. I am very surprised by this. Northern saw-whets are more commonly found much farther north (as their name implies), and this is the southern extent of their range. Carrie has trapped them on Manitou Island in Lake Superior, where they migrate by the thousands, and on Mount Manzano in New Mexico. Nonetheless, there’s one here.

Here, on Pine Mountain, both the saw-whet owl and the sugar pine are at the edges of their respective ranges, and it makes me wonder how the pines are doing. Is it my imagination, or are the sugar pines here shorter than the ones I’ve seen at Lake Almanor? Are the cones smaller? They certainly seem to be; I’ve collected some very large ones from Lake Almanor for use as Christmas mantlepieces. Cones roll downslope and are trapped by dead and down logs, but I don’t see any absolutely huge sugar pine cones, just moderately sized ones. It also occurs to me that I have not noticed any young sugar pines here- is reproduction less, or declining because of climate change? A little inspection, however, reveals young sugar pines, with their characteristic bundles of five needles, in small groups, ranging from one to several feet tall. That’s a good sign, but all the same I worry about climate change. My realtor friend Scott tells me that housing markets contract first at the edges, during a downturn. Will that occur to sugar pines here on Pine Mountain, as their pocket of cold and snow, at the southern end of their range, becomes less hospitable to them due to a warming climate?

As of now here is little evidence of human impact in the sugar pine stand at Pine Mountain. The area abuts established wilderness, and wilderness designation is one of the most effective conservation tools for public land management in the U.S. It allows federal lands such as those in Forst Service and Bureau of Land Management holdings to be managed in a hands-off manner, much more like national parks are managed. Although Pine Mountain is not itself in designated wilderness, it does lie in an area managed according to the Roadless Area Conservation Rule. The Rule, enacted in 2001, precludes not only roadbuilding but also industrial-scale logging of large, mature trees in areas under its designation. In the Los Padres Forest alone there are 37 areas protecting 635,000 acres under the rule. But the Trump administration wants to eliminate the Roadless Rule, and has begun the process to do so. Their initial proposal came with a mere 21-day public comment period (the typical review period is 90 days) and this a cynical rush-job. The next review period will be longer, and thank goodness environmental watchdog groups such as Forest Watch are on top of this.

Pine Mountain and the other areas protected by the Roadless Rule may or may not survive that rule’s elimination. So far, of the 600,000-plus public comments submitted, the vast majority have been against the rule’s elimination. But of course, that means nothing to this administration. Their fierce determination to destroy the environmental safeguards enacted over the past 60 years (see elimination of critical habitat for endangered species, removal of greenhouse gases as pollutants, revival of the coal industry, wanton destruction of the solar energy industry, etc.) brooks no compromise, and is immune to public opinion. The specter of more roadbuilding and large-scale logging in the Pine Mountain area is dismaying to me.

The effects of climate change will be more insidious and longer term. The pocket of cold and snow that is the north slope of Pine Mountain will warm and become less hospitable for sugar pines. Older trees will linger, but increasing heat will stress them, bark beetles may infest weakened trees, making conditions ripe for a stand-replacing fire. Reproduction and recruitment of young pines may wane under the drier and warmer conditions.

I will not inform the nuthatches and chickadees of these impending changes. They will know soon enough. Let them have their way for now, undisturbed, hunting insects on the boles of these imposing forest giants. Pine Mountain is somewhat of a refugium site, a spot where sugar pines exist apart from the major portion of their range, a relict from past cooler climes. I realize that it has been a refugium, or at least a refuge, for me as well. Like the birds, I will enjoy it while I can.